Milo Tyranne

Character

This is the development thread for Island Ease and Island One, two large Miln space habitats. Over the course of the next 20-30 posts, I will be detailing the history of these large space stations, including their construction, renovation, and rise to prominence after the Miln-Imperial War.

So, without further ado, let's get started.

It was here, at this time, that an outspoken Miln scientist, Professor Tomias Milo, first proposed that his species could leave their world to settle outer space via the construction of enormous artificial habitats in orbit. Tomias had written a book with the dry title of "On the Prospect of Miln Habitation in High Orbit", but which had captured the public imagination with the phrase "High Frontier", the way the Professor described space; as a venue for development and colonization on a grand scale.

At the time, it had only been a few short decades since the Miln had achieved space travel in the first place; in 350 BBY, they had orbited their first artificial satellite with the use of a giant cannon, subsequently launching more sophisticated devices and later piloted spacecraft via chemical rockets. Miln astronauts had walked on both of their planet's moons within 20 years, and 10 years later had established a semi-permanent outpost on the nearer one, in addition to several space stations orbiting Hafnip, mainly used for research purposes.

Professor Milo's proposal was much more ambitious than anything the Miln had done in space up to that point, of course. It would require massive new infrastructure to be built in orbit, as well as on one or both of Hafnip's moons.

Milo took great pains to extol the benefits of such an undertaking as space colonization; at the time, the Miln were struggling with overpopulation in many parts of the world, as well as less abundant natural resources and environmental damage caused by industry and urban development. These were all problems the colonization efforts could solve; natural resources were abundant in space, with virtually guaranteed return on investment to anyone who attempted to extract them from the moons or asteroids. With the construction of space habitats, virtually unlimited living area at any population density desirable could be achieved, allowing migration of excess population from Hafnip, not only affording the immigrants a greater amount of living space and higher standard of living, but reducing the strain on Hafnip's ecosystem in the process.

Of course the project would be monumentally expensive, at least in the short term.

Milo's proposal was actively supported by many members of the scientific community, though he knew this would not be enough. Determined that he would see the project started within his lifetime, Tomias began to pitch his idea to commercial interests, stressing the untold wealth to be found in resources and new manufacturing methods in space, not to mention the fortune in aerospace contracts to be had closer to home.

Oddly enough, the project was not difficult to sell to the general population. Besides general dissatisfaction with then current living conditions, the Miln had never been at the top of their planet's food chain; even in spite of their technology, the Miln still found themselves preyed upon by the monstrous predators which inhabited their world along side them. Space habitats sounded like just the thing; being located in space, the inhabitants could be truly safe from the dangers faced by those on the ground.

Though the project would take decades, and many would not live to see it come to fruition, younger generations would inherit a safe and bountiful future.

So, without further ado, let's get started.

- The High Frontier -

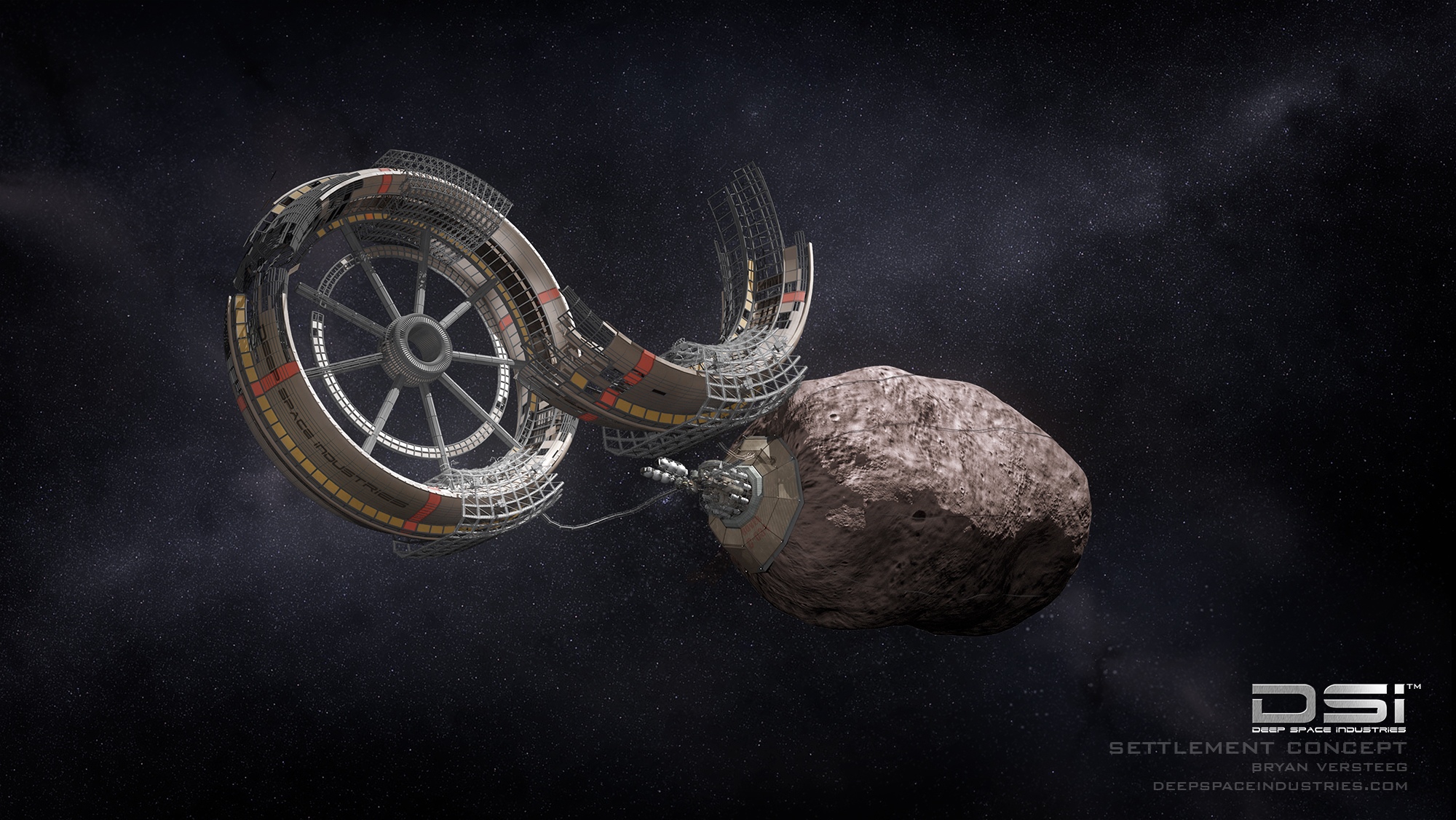

Early "space workshop", in orbit over Hafnip.

"Clearly our first task is to use the material wealth of space to solve the urgent problems we now face on Earth: to bring the poverty-stricken segments of the world up to a decent living standard, without recourse to war or punitive action against those already in material comfort; to provide for a maturing civilization the basic energy vital to its survival."

_ Doctor Gerard K. O'Neill, The High Frontier, 1976 AD.

"We stand now at the limits of our terrestrial civilization. We have made great strides over the last few centuries of our development, but in recent years, we have run into barriers: overpopulation, the degradation of our ecosystem, the dwindling of our natural resources.

"But all barriers can be crossed; it is only a matter of climbing. So we must go up; to orbit, to the stars. To the High Frontier, where finally we might achieve the way ahead."

_ Professor Tomias Milo, address to the Hafnip Global Institute of Aerospace Research, 300 BBY.

The story of Island Ease, and indeed, of the Miln presence in outer space, dates back nearly three centuries before the Battle of Yavin, to an obscure corner of Wild Space not yet visited by the outside Galaxy.It was here, at this time, that an outspoken Miln scientist, Professor Tomias Milo, first proposed that his species could leave their world to settle outer space via the construction of enormous artificial habitats in orbit. Tomias had written a book with the dry title of "On the Prospect of Miln Habitation in High Orbit", but which had captured the public imagination with the phrase "High Frontier", the way the Professor described space; as a venue for development and colonization on a grand scale.

At the time, it had only been a few short decades since the Miln had achieved space travel in the first place; in 350 BBY, they had orbited their first artificial satellite with the use of a giant cannon, subsequently launching more sophisticated devices and later piloted spacecraft via chemical rockets. Miln astronauts had walked on both of their planet's moons within 20 years, and 10 years later had established a semi-permanent outpost on the nearer one, in addition to several space stations orbiting Hafnip, mainly used for research purposes.

Professor Milo's proposal was much more ambitious than anything the Miln had done in space up to that point, of course. It would require massive new infrastructure to be built in orbit, as well as on one or both of Hafnip's moons.

Milo took great pains to extol the benefits of such an undertaking as space colonization; at the time, the Miln were struggling with overpopulation in many parts of the world, as well as less abundant natural resources and environmental damage caused by industry and urban development. These were all problems the colonization efforts could solve; natural resources were abundant in space, with virtually guaranteed return on investment to anyone who attempted to extract them from the moons or asteroids. With the construction of space habitats, virtually unlimited living area at any population density desirable could be achieved, allowing migration of excess population from Hafnip, not only affording the immigrants a greater amount of living space and higher standard of living, but reducing the strain on Hafnip's ecosystem in the process.

Of course the project would be monumentally expensive, at least in the short term.

"I say, not a decicredit for this ludicrous fantasy!"

_Representative Millian Prozmir.

Milo's proposal was actively supported by many members of the scientific community, though he knew this would not be enough. Determined that he would see the project started within his lifetime, Tomias began to pitch his idea to commercial interests, stressing the untold wealth to be found in resources and new manufacturing methods in space, not to mention the fortune in aerospace contracts to be had closer to home.

Oddly enough, the project was not difficult to sell to the general population. Besides general dissatisfaction with then current living conditions, the Miln had never been at the top of their planet's food chain; even in spite of their technology, the Miln still found themselves preyed upon by the monstrous predators which inhabited their world along side them. Space habitats sounded like just the thing; being located in space, the inhabitants could be truly safe from the dangers faced by those on the ground.

Though the project would take decades, and many would not live to see it come to fruition, younger generations would inherit a safe and bountiful future.